We all know the Outer Banks runs on tourism. As of 2022, Dare County’s $1.97 billion industry accounted for 45 percent of all jobs — and offset every resident’s taxes by $3,700. At the same time, more people means more problems, especially for a destination built on relaxing beach vacations. How does a community feed that economic engine but still maintain its unvarnished appeal?

That’s been the focus of the Outer Banks Visitors Bureau ever since COVID brought in record numbers — and a few more headaches — resulting in a Long-Range Tourism Management Plan and 19-member Task Force. Their 10-year vision? By 2033, “the Outer Banks will be idyllic island communities where residents and visitors coexist and thrive thanks to thoughtful efforts to balance and sustain quality of life with quality of place.”

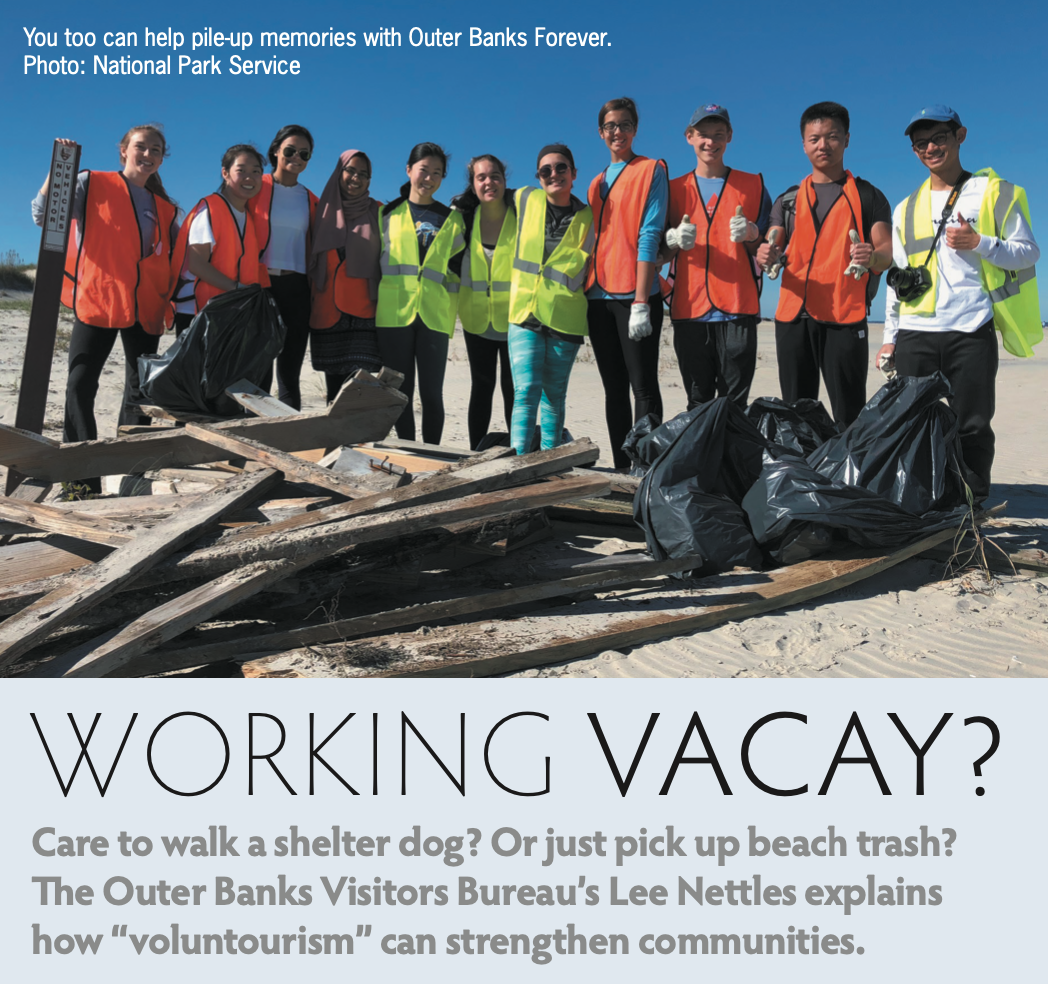

One of the task force’s earliest and most visible efforts is a push for “voluntourism,” where they invite visitors to pitch in with local nonprofits. Besides spreading awareness, they’ve worked with the Outer Banks Community Foundation to establish and promote a nonprofit directory that allows folks to directly engage with 90-plus organizations.

“It seems like we’re increasingly running into groups or families that are asking if there are any projects or things that they can get involved in while they’re here,” says Outer Banks Visitors Bureau Executive Director, Lee Nettles. “In thinking more about ways the influence of tourism can do more tangible good in the community, it occurred to us that we’ve got the relationships with the nonprofits already — what if we could connect the visitors directly?”

We asked Nettles to help us better understand how nonprofits, volunteering and tourism fit together — and how the Outer Banks can benefit as a whole. — Terri Mackleberry

This interview took place in April 2024. An edited version appears in Outer Banks Milepost Issue 13.2

As part of the long-range tourism marketing plan, I see that you’ve created a new level of partnership with nonprofits. You’ve established the nonprofit directory, you’ve been hosting mixers and workshops, or you’re planning to do that, and you’re encouraging volunteerism. I’m curious, how do the partnerships with the nonprofits fit into tourism?

I think the voluntourism is the most direct connection. So by working with nonprofits, we’ve been able to highlight opportunities where visitors could actually volunteer, whether it’s at an event or at an attraction or a specific project, like a beach cleanup or something like that. It gives visitors an opportunity to, well, show their love for the place for one thing, but just form a deeper connection with it. It seems like increasingly we’re running into groups that are coming out here or families that are asking if there are any projects or things that they can get involved in while they’re here.

OK, so let me go back real quick. So with creating the nonprofit directory, was that necessary to set up the voluntourism concept or was that something that you would have done anyway?

It was necessary for the voluntourism part. I should have pointed out, though, that we’ve always had a strong relationship with nonprofits through our grant programs. The event grant program and the restricted fund grants that we that we have. You know, those have reinvested more than $20 million back into the community over the years. And I think we’ve given awards to more than 150 nonprofits and 700 individual awards to those nonprofits and governmental entities. So we always had that relationship and it’s contributed to great projects up and down the beach, but really coming out of COVID and considering where we f thought we were going to get to with long-range tourism management planning, we just started thinking more about ways in which the visitors bureau could redirect the power and the influence of tourism to do more tangible good in the community beyond just those dollars and projects.

And, and it occurred to us that, hey, we’ve got the relationships with the nonprofits already. What if we could connect the visitors directly with them. And, you know, that we were also really fortunate as a community to have so many great nonprofits here doing work in a lot of different ways.

Originally, we’re sitting around a table and I was thinking, hey, what if the Visitors Bureau staff all wore the same colored shirt when everyone volunteered. You know, it would have more of a tangible view on tourism’s participation and positive impacts instead of just negative. And it occurred to us that, you know, I mean, we are only talking about, like, 10, full time staff at the time and in some part time staff. So when we, when we realized, hey, I mean, there, there are 100, nonprofits out here, and they’re doing a bunch of great things. If we can, connect the visitors directly with them, then it helps us in a lot of different ways, aside from just the volunteering, it makes the visitor more aware of all the work that’s gone into keeping this place special. And so we felt like, if we can just connect them with the nonprofit stories, then the visitors will become more aware of the area and become better stewards of the place, which we expected was going to be the focus of the the long range planning. The long range planning, just boiled down was the simple recognition that tourism causes not only positive impacts, but negative impacts. And so what can we do to manage both of those over time in a way that we don’t kill the golden goose? Or or just make the experience bad for visitors and residency?

Did it factor into the planning of this that it would change some of the locals’ views, maybe soften some of their views, of the tourism bureau?

I mean, we were, we were hopeful of it. Because we’ve always had these grant programs and the Tourism Board has contributed to all these great projects and millions of dollars. And, and then, and then we have these annual round-ups where we talk about our ranking within the state and the $2 billion industry and almost half of the jobs in the county. But, all that stuff, even the grants is just talking about money in big numbers, it’s hard to make it real. And it just doesn’t cut through. So our goal with all this was to just use the influence of tourism to have more tangible and direct benefits for the people that live here. And we felt like, it was kind of in keeping with a state motto “to be rather than to seem.” Let’s just not rely on press releases and big numbers and all that stuff, let’s just do the start doing this. And, we’re hopeful that would have a real impact. And, I mean, the perception of the visitors bureau and the Tourism Board is a byproduct. But the main thing is that we’re able to do what we do best, which is communicate with visitors, with hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of visitors and make them aware of the nonprofits and get them involved through the nonprofits, then if we could do that it was going to have make a profoundly good impact on our community. And, we were able to stay focused on our legislative mandate of promoting overnight visitation with an emphasis on less than peak months. So we felt like it was just it was a real, I don’t know, just the solution to things that we’ve kind of been running into for so long.

OK, so it’s a great idea, and how exactly did it come about? Was it people asking for opportunities? Have you heard of this in another area?

To the best of my knowledge, we’re the only community that’s embraced it in this way. I mean, other communities have done tourism management plans. That’s, it’s that part of it’s sort of catching on, but we, I mean, it was literally me and a couple of my staff folks sitting around a table, and I had this notion of tourism for good. And I had just written it down on a little piece of paper and had it on my desk. And so we’re talking about that, like, how can we do that? Aside from the industry, aside from the jobs, aside from the money, how can we, how can we use the power and influence of tourism to do more good in the local community? So we just, we just kind of hit on it that. I mean, we’re talking about the grants and everything, but it was still talking about money. So the nonprofits are already doing so much good. So we’re just leveraging the relationship that we had with them already. It didn’t cost us anything extra, but it helped in our profits, it helped visitors get a deeper understanding of the place and a more enriching experience. So it’s just like, a win win win that didn’t, didn’t really cost anything. And the coolest part about it all has been to see how it’s been received by our local community, the nonprofit organizations, but also visitors. I mean, we had this idea, and we started trying, with each of the programs that we were developing, we would think, well, is there a way to tie this into a nonprofit?

And we started with our social media posts, and some of our advertising was started, like connecting things to nonprofits. Like instead of just promoting an event, like we’d always done, we started describing the nonprofit that was the beneficiary of that event that was behind it. So it’s given visitors and other reasons that go and helping to get the story out. But, we started working on Outer Banks Forever, the National Park Service Group, to do like some shared webcast or social media groups, like when they did a sea turtle nest excavation, and we just did a webcast to our social following, which was, you know, is really big. So we were able to help them kind of amplify what they were doing. But meanwhile, we, we didn’t really know how it was gonna go. We didn’t know how it would be received by the visitors, necessarily, but it was, it was popular, and people were just totally engaged in it. And we found that again, and again, as we’ve gone along that the more people love it here, but so then it’s on us to help them enhance their understanding of the place and its people. So it’s been, it’s been cool. I mean, we had a hunch, but when it started proving out that visitors were genuinely interested in it, it’s, it’s been real satisfying.

So how long has this been this concept been being worked with at the bureau?

I would say, I would say probably for the last six months.

And then exactly what responses are you seeing? Likes on social media or actually turning it around into people volunteering?

We’ve grown the nonprofit directory to over, I think, around 90 nonprofits. And when we started off, there were only a couple that had volunteer opportunities. And now if you go there, it’s, I mean, there, there are quite a few of them. And we were hopeful that it was the kind of thing that would just kind of grow and mature over time. And it seems like that’s happening.

As far as the promotion goes. It’s yes, it’s likes and, and shares, and comments and stuff like that, but, but it’s also the types of comments that we’re getting. The level of engagement is just much greater. I mean, for better or worse. It’s like our old social media posts, you could count on people just chiming in, or regardless of what the post was about, they would chime in I love the OBX! or something.

But with this. We did a video of Island Farm and it’s, you know, that’s not one of the top 10 must see or dos. It’s a deeper, it’s a much deeper cut on the Outer Banks, and sharing it with visitors, I mean, people were really interested in it, they were just actively talking about how they didn’t they didn’t know it was there, and they are going to add it to the list next time around.

Was there a volunteer opportunity connected to that?

Oh, uh, not that specific post. But um, you know, there are quite a few of them that are listed through that nonprofit directory, and, and also through, you know, the normal event calendar. Now we’ve got, like, before, we never had the connection back to the nonprofit, just the event, the dates and whatever.

Right, I see.

So and, you know, I mean, as far as what we’re talking about goes. I hope that, like I was saying, that it will continue to mature. And part of that’s just our local community and the nonprofits becoming more aware of what we’re doing and why. And I think it’s the kind of thing that it, you might not have an idea right now. But as we go along, hopefully, more and more folks will have ideas about how to utilize visitors coming into the market in a good way. It’s, I mean, I realize that it, it is somewhat of a burden for the nonprofit to figure out how to how do I bring in this new crop of people?

That was one of my questions for you.

Yeah, and training what they do and, and all that. Pperationally it’s, it’s a little tricky to get initially, but once you figure it out, then you’ve got you’ve got this system in place, and we’re promoting it for free. And the other part about the whole promotion of it, aside from just our website, and social and email, is that there’s been a lot of interest in it from the writers side. So travel writers that were that were hosting and in contact with.

Ok, alright, I do have some logistical questions. I’ve been on there, and I kind of used it as if I was a visitor wanting to volunteer. So I go and I see the volunteer tab at the top of the page. And then like it takes me to all these different nonprofits, which is it’s amazing to see how many we have. And then there’s a button that I can click on if I’m interested in volunteering. But, I gotta say, the onus was on me to find the opportunity. So I was like, oh, okay, so I gotta go to the Elizabethan Gardens and fill out their paperwork, or I’ve got to go to the aquarium and fill out their paperwork. It seemed like the level of frustration could be high quickly. With trying to learn if your trip, none of your accommodations, line up your, you know, the dates, and then like, Oh, I got a line with a volunteer opportunity to and I gotta work with all these different organizations to try to find the one that works for me.

Yeah, so I get that. I think there’s definitely room for improvement. But that’s kind of the whole point is that this is not done, you know, it’s, a work in progress. But I’m real optimistic, just from the traction that it’s gotten in the short amount of time that we will get there. And part of that’s on the Visitors Bureau too, you know, I think that we can do more to like, I mean, there are different software, for instance, that that coordinate volunteering efforts better, so I mean, we’ll, we’ll stay active and looking into that and seeing if we can help bring our partners along.

And another part of the puzzle is the potential for connecting the for-profits into this effort. Because, we live in a really generous community, of course. Like, practically every for-profit business, in the tourism industry has nonprofits that they support, but in a variety of ways, but they don’t generally get a credit for that and they, more than likely, they haven’t been looking for ways to promote the connection with the nonprofit to their visitors. So it wouldn’t be just us with our, our directory calendar and volunteering. I think that we can quickly get to a place where rental companies, for instance, are developing travel packages that include projects and things like that.

Are there any thoughts about having some volunteer opportunities that are already lined up? Like beach cleanup from 8 to 12 on this day, then people can just go directly to it and sign right up for it so that it’s easy to do. Instead of having to go find a volunteer activity for yourself.

Yeah, I think so that I mean, ideally, I’d like to get to a point where we have volunteer opportunities that are being sorted by date, time or interest. I mean, maybe maybe I don’t like going outside, maybe I’m more of a history culture person, and I want to contribute in that way. Maybe I like live music I want to contribute. It’s kind of a little modeled after, like, touring bands and stuff like that a lot of them will have green teams or at festivals, you get free tickets to the festival, and then you’re giving up your time to clean the place or do whatever.

But I agree with you completely. It’s, it’s clunky right now, it’s got a ways to go. But I think that the interest is there from all sides from the nonprofit, from the for-profit, from us from the visitor. And you know, we’re not forcing this on anybody. I think it’s something that all parties involved want to do. So I’m confident that there’s a way to do it better.

Right. Because the nonprofit doesn’t have to put a volunteer button on their page. They put it up there if they want volunteers. So, we don’t really have this type of thing, like a volunteer clearinghouse for locals either. Like, a specific site where a local can go and just kind of browse and say, Oh, I’d be interested in that. So are you marketing this to locals as well?

Yeah, certainly. I mean, and kind of back to one of your earlier questions, I guess your question was about is this intended to change the perception of the visitors bureau, the tourism board, but I would kind of step back even further and say, part of our intention was to just close the gap between residents and visitors. And what better way to do that when you’re standing side by side with somebody and you’re both, you know, sticking your hands in this project and trying to make it better. That breaks down the walls, it’s a whole lot harder to throw rocks at somebody that standing next to it, you know, so that was that was a part of this as well as like. And, and we’ve had meetings with the nonresident property owners too. I mean, they are another group that just like perception, and, there’s just a gap between locals and nonresident property owners. But the thing that we all share is our love for this place. So let’s just quit, you know, making up what we think about other groups, and let’s just get together and start doing good things for the Outer Banks.

That’s great. Yeah, I agree. So for somebody who was reading this article, can you give some examples of what volunteers are actually doing and a few examples of what is needed?

Yeah, we’ve done beach cleanups. Several of those had been listed. I mean, you could do like seagrass planning. That happens at different times. You can go to the Elizabethan Gardens and work with their grounds. They do plantings and things like that. The SPCA has dog walking and just any number of things. So. I mean, I think I think it varies dramatically. And you can help out with an event if you’d like to. I mean, you’ve been involved in events before they take a ridiculous amount of work. vents don’t happen for the most part, just for the fun of it. Most of the events happen because they’re a fundraiser for a nonprofit. So, you know, the thing that we can do to help nonprofits is to give them an extra set of hands or give them access to new potential donors.

Okay. And I think you kind of answered this before earlier. But like, I guess there’s the possibility that nonprofits could get overwhelmed with helpers, and not have the staff to, you know, to manage that, but I guess that’s something that’s just part of the clunkiness that has to get worked out.

Yeah, I mean, can a nonprofit really have too many volunteers? I guess it’s more a matter of just spreading them out as best you can. Or you could always just say, We’re full right now, or turn off your your volunteer button on our site, if it becomes too much of a hassle. But I just think it’s a growing process and our community’s growing, our visitation is slowing, but still growing. So I think that this is an effort that helps us direct the positive impacts of that growth, instead of it just like, kind of happening to us.

OK. How are you tracking success with the program? Like how do you know if volunteers are signing up? Because they’re going directly to Elizabeth Gardens? Or they’re going directly to Community Foundation? How do you know that they are actually volunteering? And how are you going to track this?

Initially, we started sharing the idea with the nonprofits just to see how they reacted to it. And then, kind of early on, we developed a partnership with the Community Foundation, just recognizing that they had great relationships throughout the community, with the nonprofits that they work with. So it’s like a, it was a great partnership. And we’ve been really happy with how that’s matured as well.

And we’ve seen the number of nonprofit entities on the directory increase, we’ve seen the volunteer buttons increase dramatically since that inception, and we’re just talking to people, we’re talking to the nonprofits to see how it’s going for them. And that’s part of what comes through with, with the mixers and the knowledge series that we’ve, with the Community Foundation’s partnership, we’ve been able to put together. So the idea behind that is we’ve got all these great nonprofits, most of them are fairly small staffed. So let’s bring them together and help give them the forum to learn from one another and support one another. And we’ve brought in some speakers to help with training and stuff like that. So, I mean, all of it’s just intended to make our already great nonprofits even stronger and give them what they need to be sustainable over time. So the short answer is, most of it’s just anecdotal.

Okay, and with the cost of setting up with nonprofit directory, is your board looking to you to provide any kind of metrics to balance out that cost?

There wasn’t really a cost associated with it. I mean, we had staff already that was dealing with the website back end, and we were able to set it up in the CMS and the front end easily. So it’s just and we’ve been able to sort of share our communications with the Community Foundation and work with each other’s databases. And so that’s, I mean, that’s part of the beauty of it is that there hasn’t been a real expense with it. It’s more a matter of rethinking how we go about our business and how we promote the destination.

Okay.

So for instance, an example of that is we run an ad in the state’s travel guide every year. Last year, or this year, we did an ad that had Jockeys Ridge is the main visual, which is, you know, that’s nothing surprising it’s one of the state’s most popular attractions. But instead of just having a branding tagline, we told the story of Carolista Baum and how she stood up to the bulldozers and the development and, through a grassroots effort was able to generate petitions and establish legislation that created the state park. Well, that’s a pretty cool story. That tells me, it tells me more about Jockeys Ridge as a visitor. It tells me a lot more about the community and what makes this place so special.

And then we had a little QR code for finding out about other nonprofits in the area. I didn’t cost us a thing, it’s an ad we would have already done. But in, in my belief, we’ve made the ad more compelling, and more really, descriptive of what makes our area special. So it’s just kind of a rethinking of what tourism can mean on the Outer Banks, I think, in the promotion of it.

OK, I’m going to ask you the cynical question. What would you say to the cynical person who said, Okay, this is just another marketing ploy for the visitors bureau to make them feel better about bringing more people here. Or it’s just another strategic way to market the Outer Banks. How would you respond to that?

If getting more volunteers and potential donors for our nonprofit organizations is, is a bad thing, then we’re happy to be guilty as charged. You know, that’s the beauty of it is that it, it is marketing, but it’s marketing with a purpose. And it’s not just pimping the destination, it’s, it’s recognizing and celebrating what makes this place so great. And, and it’s also giving visitors the tools and the understanding to be better stewards of this place, and to just appreciate who we are living here. So at the same time, I mean, the Visitors Bureau, the Tourism Board, are created through state legislation. My organization exists to promote overnight visitation to Dare County, so I can’t not do that. But what I can do, also, is rethink how we do that so that it manages the negative impacts. And if I can get more people, more hands, more dollars involved in helping to preserve it and take care of it. I gotta believe that’s a good thing. That’s, that’s satisfying the law, but it’s also just redirecting the power of tourism for good and community. So I mean, cynics will be cynics but that, I think that it’s not just Lee saying something. It’s not just us promoting something. It’s people showing up at beach cleanups, it’s people, you know, showing up and helping actively lending hands. To be rather than to seem.

Okay, great answer. Have you ever volunteered on vacation? Or is that something that you would do?

I don’t remember like specifically volunteering on vacation. I’m kind of more of an intermediate contributor, I guess. Like, for me, I like to lead by example, like when I see trash in a parking lot or something, I pick it up, or I see trash on the beach, I deal with it. I think if everybody just has a sense of personal responsibility and the Golden Rule, Do unto others as you have them do unto you, it gets us pretty far down the road. But I mean, I think we’re kind of a trailblazer as far as this goes, I would say even if even if I weren’t specifically volunteering in different destination, I think I would appreciate understanding sort of the nonprofits and some of the causes that are that are behind different places. I think it says a lot about an area.

Definitely. So it sounds like there’s already been some success, but if, if there wasn’t immediate success, something that would be metrically trackable, would you just stop doing this? Or would you hire a staff member? Or what’s the future plan for making this grow?

Uh huh. I think that the most important part of it. Well, really, the most important part of the whole long-range tourism management plan, is developing the relationships between people. So closing the gap between residents and visitors and, you know, more specifically, with the voluntourism stuff, closing the gap between the visitors bureau and the nonprofits and between the visitors and the nonprofits. So it, it’s an interesting effort, because I don’t think that it has like, a beginning, middle and end necessarily. I think it’s just something that it’s, it might be idealistic, but I want to change the culture of what tourism means on the Outer Banks. It can be a positive thing, I believe, and we’re a small enough community to make that happen. So I don’t see it being as like a two-year marketing campaign or whatever, I think it’s just a change, a fundamental change in the way that we do business.

Okay. And then if locals, nonresident property owners, nonprofits, visitors, whoever is reading this article, what can we all do to make this a success? What can we all do so that it is successful?

All right, find out more about your local nonprofits and look for ways to lend a hand or help the cause. There’s so many great things going on out here. And it’s a great way, like … a lot of times visitors will come into contact with us and they’re like, I want to, I want to know where the locals eat or what the locals do. What a great way to find out what the locals do. Go volunteer with them, you know, or learn more about nonprofits they’re involved. So just hopefully, we’re starting to provide a place where people can find out more about this, or one way that people can find out about the nonprofits. I mean the Community Foundation’s also involved, they’re, I don’t want to just limit this to us. I think I would just say, to find out more about local nonprofits, and as much as we’re able to help that along, then we’re happy to do so. Just get out there and lend a hand. There are a lot of great things going on.

All right. Well, I’m interested to see how it unfolds. And yeah, it’s a great idea. Is there anything else or you want to tell me?

Well, I, sure said a lot. I think I would just be restating stuff that I already said. But, uh, I can tell you this though, that out of all the stuff that I’ve ever done in marketing or working for ad agencies or working with Convention and Visitors Bureau, that I’d have to say this, it’s, it’s been the most satisfying. It’s just the people that work in the travel and tourism industry, but especially folks that work at the Visitors Bureau, if we’re, if we’re doing our job well, we’re in a constant tug of war, because we’ve got business interests on one side, and we’ve got culture and just the unique characteristics of the place on the other. And if we do our job well, neither side can ever win. So it’s hard to, sometimes, you know sometimes you conflicted about that stuff. But with this, with this initiative, it just helps. I mean, I think all of us have felt a new sense of purpose and just feel good about what we’re doing. That we don’t have to separate our, our work selves from our personal selves. That’s, that’s where it can all kind of come together and just do more good.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Michele Thibodeau really wants to come home. But she can’t. It’s not because she can’t find a good paying job. (She’s got a solid tech career that lets her work remotely.) Or housing. (The Duck native boasts lots of local contacts — and two incomes to help pay rent.) The catch is she also has an infant and a toddler. And since both Thibodeau and her husband work full-time, she can’t return until she finds someone to watch the kids.

“My whole family is on the Outer Banks,” says Thibodeau, who moved to Colorado 15 years ago. “I want to raise my children there. But we’ve been hesitant to pull the trigger until we really dial in childcare. We’re on a waitlist, and we hope that something will come through so we can move back next year. We’ve run into the same issue in Denver, so it’s just something that families are navigating all over the place.”

It’s particularly problematic on the Outer Banks. Twenty years ago, there were dozens of licensed family childcare homes and centers. Today, there are seven licensed homes and 14 licensed centers. Only nine of the centers serve infants and toddlers and have no special eligibility for enrollment.

But even if you don’t have young kids, you’ve seen and felt the impacts.

As a growing number of working parents can’t find daycare or preschool programs, many must leave the workforce. For parents, this could mean ending a career you love or taking a financial hit and learning to live off a partial income. For the community, it means losing crucial employees that keep our lives and our economy running smoothly — medical staff, teachers, service industry workers, housekeepers, and first responders.

The problem is in the numbers.

According to Children and Youth Partnership for Dare County, based on July 2022 census numbers, there are 1,594 children under age five in the county but only 550 early childcare slots. These are found in licensed family childcare homes and centers. There are a number of legally operating part-day programs as well (i.e. unlicensed), but many working parents need full day care.

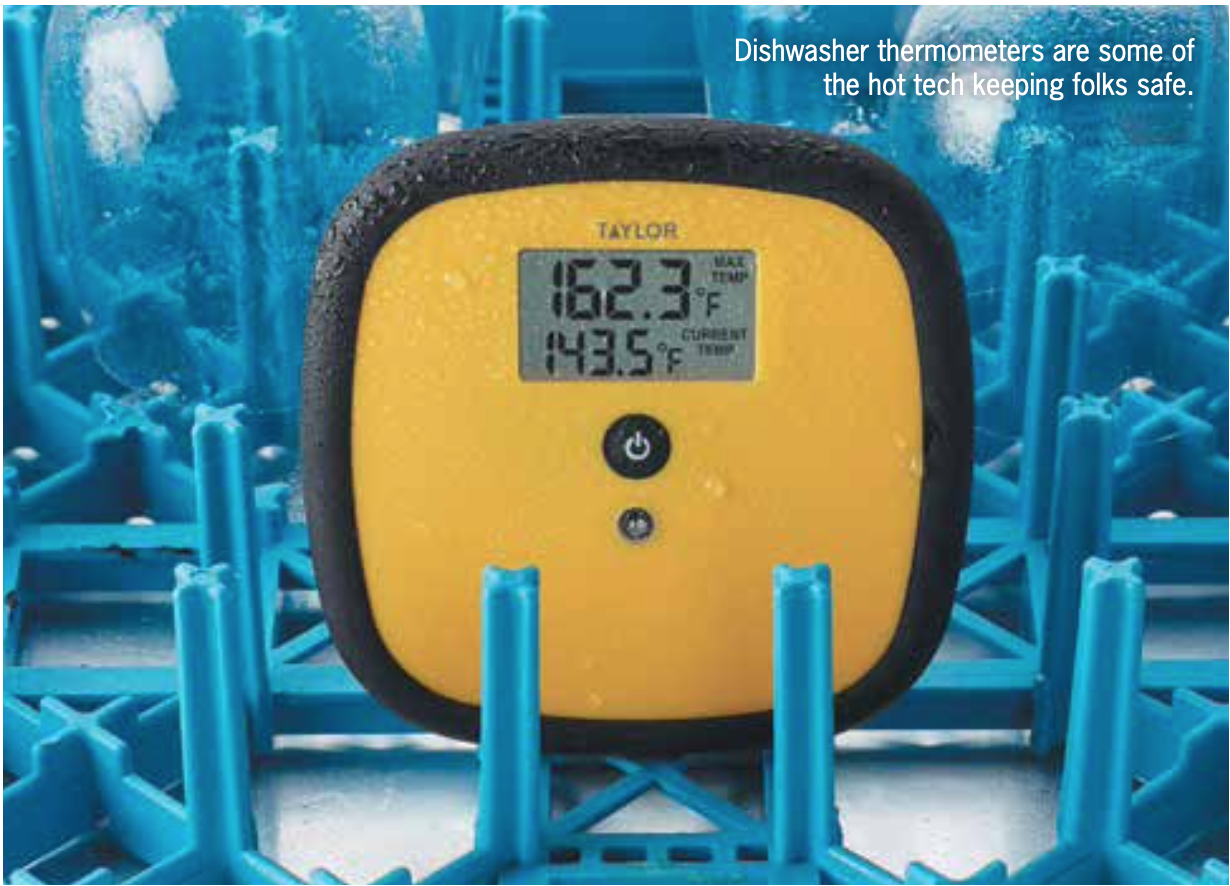

Meanwhile, North Carolina childcare providers earn just $12 per hour on average — while dishwashers make $15 to $20. Furthermore, the federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund — which provided North Carolina with a total of $3.6 billion since 2019 to address pandemic-related challenges in schools — is set to expire on September 30. Factor in population growth — from new families moving to the area in droves to local families becoming multigenerational — and the outlook only looks bleaker.

But it’s not just a problem on our little sandbar; it’s a crippling issue that impacts our entire state.

“All 100 counties in our state are considered ‘childcare deserts’,” says Susan Butler-Staub, Policy and Community Engagement Coordinator with the North Carolina Early Education Coalition. “There are not enough spots for children who need them and want them. So, it’s a pretty dire situation.”

And that just means it’s dire for all of us. For the small business owner who loses yet another full-time employee. For the restaurateur who keeps a child busy with coloring pages and crayons swiped from the host stand while their server covers a lunch shift. And especially for the toddler who spends most mornings on a tablet in the corner while their caregiver cleans cottages — instead of learning and making friends during crucial developmental years.

We asked Ms. Butler-Staub about this issue’s far-reaching ripple effect — and what we can do to help. — Hannah Bunn West

This interview took place in the summer of 2023. An edited version appeared in Outer Banks Milepost’s fall Issue 12.3

MILEPOST: North Carolina is considered a childcare desert. What does that mean?

Susan Butler-Staub: It is true that all 100 counties are considered a childcare desert in our state, meaning that there are not enough spots for children who need them and want them. So it’s a pretty dire situation. There are more than five children competing for every available licensed childcare slot in the state and that’s a really high number. In a lot of areas, that number might be higher because that’s just an average.

The Children and Youth Partnership for Dare County estimated that it’s more like eight families competing for each slot in our area.

In a lot of places it can even be 10-15 children competing for one licensed spot. People are having to think about how do you get on a waitlist before you even know you’re pregnant? I was working with a teacher in Charlotte, touring a childcare program’s infant room and there were three empty cribs. They said, ‘Oh, those are for the children that haven’t been born yet.’ The parents had gotten off the waitlist while they were still pregnant and were paying tuition to hold the spots months in advance for their unborn children.Given the cost of tuition, it shows you how desperate parents are in this childcare desert. That’s what the competition looks like.

It seems everyone has a waitlist, sometimes years long. What factors are contributing to these endless waitlists?

Across the whole state, regardless of urban counties or rural counties, we find that access to childcare slots can take between months and years to become available, particularly for infant and toddler slots. Those are the hardest to come by. So the Outer Banks is not alone in having wait lists that are over a year long.

A lot of it has to do with the staffing crisis, but not all of it. Some of it has to do with the fact that there are just not enough childcare slots or facilities for the number of children who need them. But also, because we don’t have enough teachers, you will sometimes see empty classrooms that we aren’t able to staff, so we can’t open those classrooms to serve children. That also results in a waiting list.

What are some of the barriers for teachers and childcare workers? What do you think is contributing to the loss of people in that industry?

Working in childcare is a really demanding job. When we think about the crisis we’re in right now, it’s due to a number of different converging issues. The primary issue, the biggest one that has been going on since I’ve been in the field for over 20 years now, is that folks who work in childcare are chronically underpaid. They are not paid anywhere near what they’re worth. Almost half of childcare providers are on some sort of public assistance because of how little they are paid, most don’t have any sort of health or retirement benefits, yet they’re doing work that requires a high level of knowledge and skill.

There’s so much that goes into it, and they’re getting paid $12 an hour. It’s an unsustainable situation. For a lot of providers, they may have the passion for it, they may really want to stay in it, but because they have their own families and their own lives that they have to support and sustain they can’t financially make that commitment. And it didn’t help that during Covid, places like Target and Starbucks started paying between $15-$25 per hour. We started losing a lot of folks to that.

And then there’s the issue of affordability for families. Dare County’s Child Day Care Assistance Program helps pay for childcare, but those eligible can’t even submit an application unless they are able to list a licensed childcare provider with a vacancy…

You can’t access the funding and use it because you can’t secure a slot in the right time frame. It’s a real catch 22. It’s an unintended consequence when policies like that are set up for these types of services. It makes sense when setting up the service that you would want to make sure that a child has a slot before giving out money. But it’s important to understand the context of our communities and what they look like right now–childcare slots are hard to come by. So how can we make these programs work so that families can have real access to them?

What are the alternatives as a parent? Either quit your job to stay home with children or send them somewhere you don’t feel great about?

That’s what it comes down to for a lot of people. We know for parents who choose to or need to stay in the workforce, those early years are the most critical for finding that high quality care. You know, that place where we feel comfortable leaving our children, where we feel like our children are safe and cared for so that we can leave them with confidence and go back to the workforce and be engaged in what we’re doing.

State and federal relief that got us through the pandemic comes to an end as this year closes out.** How might that worsen the situation?

The biggest thing we’re working on now is the funding cliffs that we’re facing at the end of the year. We’re waiting for the state budget to come out and really continuing to advocate for $300 million to be in that budget to support the continuation of the stabilization grants. Those really provided childcare programs across the state with the ability to increase staff pay, to provide bonuses, to provide benefits. Something like eight out of 10 of the programs who received them said that they won’t be able to maintain those raises or bonuses once that funding goes. And so, if we have eight out of 10 programs taking away the raises from their teachers, we expect that that will have a pretty significant effect on staffing in the field which will then turn into increased issues with access.

We’re really hoping to see that money in the budget, or at least some of that money in the budget, so that we’re able to buy ourselves some time to explore additional policy options. If we can continue that compensation for early childhood teachers, then we can work together with advocates and legislators to continue some discussions around additional supports for the workforce. One big one would be increasing childcare subsidy rates, so that providers are paid more per child who receive childcare subsidy, so that they’re then better able to pay their teachers. Also looking at other innovative ways to bring money to kind of fix the childcare financing system because, fundamentally, that system is broken.

We need to look at creative policy levers to fix the childcare financing system in our state, and also to advocate at the federal level to try to get Congress to send money down the pipeline, because it’s not just a North Carolina issue. Pretty much every other state is in the same boat, fighting for the same things and working on the same issues. Continuing to advocate at the federal level in hopes that we can get some federal legislation that will bolster the childcare industry as well.

Is there room for individual counties to step in in regards to funding?

That’s something we’ve seen a lot more of in recent years–counties coming up with creative solutions that really fit their community’s needs. Counties are starting to think about it in terms of economic development. As advocates are speaking up on the issue, they’re starting to realize that everything is linked to child care: If people want jobs, they have to have childcare. If people want to go back to school, they have to have childcare. If we want to bring in new business, we have to have a strong childcare structure–all of it is linked to this service. That’s really spurred a lot of these new conversations because for a long time it was overlooked.

This is not something that’s fixed at the national level yet. A lot of folks are saying, ‘we’ve got to fix it for ourselves, we’ve got to figure out what we need in our area.’ It will take counties thinking creatively, looking at the childcare needs in their communities, and looking at what resources are available to do something that maybe hasn’t been done before. These are the steps a community would need to take in order to move the needle.”

While everything is in the works, what can we as individuals do to help in our own communities?

A lot of people just don’t talk about childcare, so many people don’t know that it’s an issue. Unless you’ve had a child that needed childcare, you don’t understand the impact of it and the ins and outs of it. We’re always telling folks just to talk about it as much as possible because the biggest part of advocacy is public awareness. Whenever you see people that have any sort of power within the community–at church, or in the grocery store, at the mechanic–talk about childcare with them. Talk about the struggles that you’re facing and share your experiences. Continue to have those conversations locally so that when you speak at those county commissioner meetings people aren’t surprised anymore but instead say, ‘What do we need to do about it? What are the next steps?’

_________________________________________________

Swells’a Brewing always knew they wanted to do more than just sell beer. They also wanted to make a lasting difference for their Outer Banks community. That’s why they joined “1% for the Planet,” a program that allows businesses to kick back a portion of profits to an environmental cause. Last year, the KDH brewery had a check ready for $11,550. The only question? Who to make it out to.

“We wanted to support our national parks, because we feel they’re the last places on the Outer Banks that keep everything natural and remind people of why we live here,” says co-founder Sam Harriss. “And Outer Banks Forever provides the mechanism to help them more directly.”

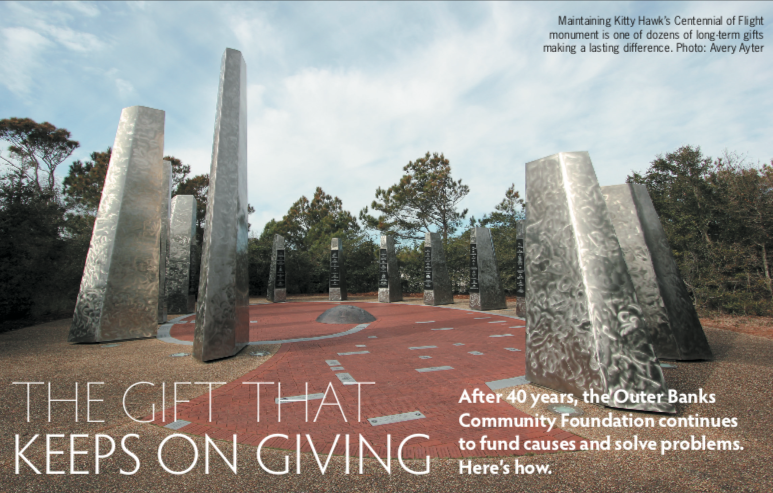

Launched in 2019, Outer Banks Forever is the official non-profit partner of NPS’s Outer Banks Group. Often called “friends groups,” at least half of America’s 422 national parks has one to help perform myriad tasks. Some handle educational tours and run volunteer groups. Others simply promote educational awareness. Nearly all perform one primary function.

“Most friends groups do some form of fundraising,” says Outer Banks Group’s director, Jessica Barnes. “National Parks can’t ask for donations— if they need funding for a specific project, they can’t go to the public or to a foundation or to a business and ask for money.”

But Outer Banks Forever can. And they do, tapping everyone from weekend visitors to longtime local businesses to sneaky federal grant programs. Furthermore, they often find ways to get around red tape that bogs down most government bureaucracies, helping make improvements that might otherwise take years, whether it’s installing the first hand-capable kayak launch on Hatteras Island or adding a mile of multiuse path to a busy Buxton thoroughfare.

“Our Pathways to Your National Parks campaign will connect Route 12 to the Old Lighthouse Beach site and to the current Lighthouse,” says Barnes. “That project has been on the park’s wish list since 1984. And they just didn’t have funding or the capacity to be able to make it happen. And this year, we are going to be giving the parks about $400,000 for the Pathways Project and several other smaller projects.”

We asked Barnes to better explain how friends groups work and — more importantly — why folks should help.—Matt Walker

This interview took place in April of 2023. An edited version appears in Outer Banks Milepost Issue 12.2.

OUTER BANKS MILEPOST: So what’s your background? And how did you get what sort of got you into this field? I guess.

JESSICA BARNES: Yeah. So I have been working in the nonprofit sector pretty much since I got out of college, back in 2006. So I started learning kind of fundraising and nonprofit marketing, volunteer management, with a breast cancer organization in Richmond, Virginia, and then just sort of have grown my career since then. I did move out to San Diego for a few years, I got my master’s in nonprofit management and leadership from the University of San Diego, and then was looking to move back to the East Coast. I’m originally from the Richmond area, Mechanicsville, Virginia, to be exact. And when I was looking to move back, that was about 2015, I came across a job posting at the Shenandoah National Park Trust. And that was my first foray into nonprofits that support national parks, I didn’t really know that that was a thing. So I started as the Director of Development at Shenandoah, which is based in Charlottesville. I was there for about four years, and then this position came up.

So we are actually part of a larger nonprofit that’s called Eastern National. And Eastern National, they are actually a retail nonprofit. They run bookstores in national parks around the country, along the east coast and Midwest primarily. And they have been running the bookstores here on the Outer Banks and all three of those national parks here for many, many years. So they had a good relationship with the Park Service here. And there was no true dedicated fundraising partner — or friends group is sometimes what they’re called — here on the Outer Banks raising funds for all three of the national parks. And so they decided to create Outer Banks Forever, and kind of launched it as their first philanthropic friends group. And they hired me as the executive director.

So I moved down here to the Outer Banks at the end of 2018. And at that time, it was very new; we were really launching this thing from scratch. And so we launched to the public in April of 2019, during National Park Week. So National Park Week is always at the end of April, right around Earth Day.

So that’s what brought me here. But I’ve been in the nonprofit sector, like I said, for many years now, primarily doing fundraising and marketing and volunteer management and program management as well. I loved working alongside the National Park Service in my position at Shenandoah, and learning how philanthropy can support parks, and sort of fill the gap, I think our national parks are, they’re such an important part of my life, I’ve been going to national parks all my life. And that federal funding, you know, doesn’t necessarily keep pace with visitation. Particularly the past, I would say, five to 10 years, our national parks have seen huge increases across the country, in visitation and people exploring and learning about our national parks. But just because we have more visitors doesn’t mean that the parks to get more money, unfortunately. And so that’s kind of one of the roles that Outer Banks Forever is here to play. It’s just kind of filling that gap and helping our parks kind of adapt to new challenges.

That’s cool. I told you before that when I first interviewed Superintendent Hallac, that was one of his missions was to get a friends group because they do exist. They have existed in other parks and capacity for a while, right?

Yeah. I think there’s somewhere around 422 units of the National Park Service around the country. And I would say at this point close to half of them have some sort of Friends Group. Some are small, not well established; and some that have been around for a long time. I know that friends of Acadia up in Maine is a good example of one that’s been around a long time.

But even here in North Carolina, Friends of the Smokies — Great Smoky Mountains National Park — is a friends group that’s been around is very well established. They raise lots of money for the Smokies. Blue Ridge Parkway foundation is another one that’s based in North Carolina that’s been around for a long time and much more established, obviously, than we are. So we while we did start this from scratch, we are part of this bigger network that, you know, gets together every year for a conference and learns from each other and shares resources and things like that. So I have counterparts at national parks, like I said, Smokies certainly, Blue Ridge Parkway the closest, but you know, as far away as the Grand Canyon that I can call up and ask questions and learn from and see how they’re working with their parks and how they’re getting projects done and things like that. So we have a pretty good, strong network of sharing within our kind of friends community.

I guess most people, they just figure it’s a federal park, it’s already funded. Can you speak a little bit about what sort of shortfalls are really are? What’s the reality in terms of funding versus, you know, what they get versus what, what they need? Specifically with the Outer Banks Group?

Yeah, what’s interesting is, like I said, we’ve seen a big increase in visitation at all national parks. But certainly here in the Outer Banks, over the last five years, we’ve seen, you know, huge jumps in visitation for the parks. And like I said, the way that their budgets are structured — their federal budget — it’s not necessarily based on increasing for that. So what ends up happening is the parks, for the most part, they are getting, their budgets have been fairly steady over the past decade with, you know, some small increases for cost of living and things like that. But really, what ends up happening is there are more visitors using the resources and visiting the parks, but they’re having to manage those increase in visitors with the same amount of funding year over year. And that’s just a challenge when you have, you know, sometimes several hundred thousand more visitors at a park, but they don’t have more staff to manage that. And that’s everything from mowing the grass to cleaning the bathrooms to, you know, giving programs in the park.

So that’s a challenge. And one of the roles that we play is not only just sort of helping to fill the gaps, where, you know, they don’t have enough funding for a particular project or something that is really important, you know, enhancement to the parks. But also as a friends group, what we can do is we can help them access other pots of federal funding, that they can only get to if they can provide a private match. So our organization is facilitating a public-private partnership with the federal government. And so sometimes there are other pots of funding — large and small — that our parks can get access to, as long as we can provide a private match. And private can be from individuals and families, business sponsors, foundations, things like that.

And I think it is important to note, we do have one fee park here. So Wright Brothers does have a fee to get in. And that is great for a park because that is a revenue source that is tied to visitation. So more people come into the park, more people pay to come into the park, that’s more funding that they have. The challenge, though — even with a park that has a fee — is that those funds are restricted. So the park can only use them for certain things. So it’s not like they get an increase in funding and they can use it for whatever the park needs. There are specific guidelines around what those funds can be used for. So that’s one sort of distinction to think about.

And then we have here on the Outer Banks, two parks that don’t have fees. So Cape Hatteras National Seashore — first National Seashore in the country completely free to visit there. You know, there’s no entrance fee, I guess you would want to say people have to pay to stay there. Of course. Same thing with Fort Raleigh, no entrance fee. And they do have other revenue sources. For example, Cape Hatteras specifically has the off road vehicle permit process, where if you want to drive on the beach, in Cape Hatteras, you have to have a permit. That is, again, a revenue source and more permits equals more revenue. But again, that revenue is restricted. So really, those funds are used to manage that program. And I think here on the Outer Banks, when it comes to particularly that program, beach driving, it’s a natural part of our culture here but it’s this is actually something very unique to beach community to be able to drive on the beach. So the funds from that program go to support that program and to help offset the cost of managing that. So again, we get to play kind of a unique role in helping the park just fill those gaps. And I think it’s even more important now, because we are seeing such a big increase in visitation but not seeing the same comparable increase in their federal budget.

And what were you saying before? The problem is you can’t I couldn’t donate to a park, if I wanted to correct? so you guys serve the role to be able to take donations. Not only can you free of how this money is used, you can actually solicit money to be donated. Do have that correct? So why can’t I just donate to the park directly?

Yes, sort of. So you can, if you wanted to walk up to the park and give a donation, you technically can do that. It’s just harder on the park side. Number one, they can’t ask for donations. So we’re the only ones that can ask for donations. So if they needed funding for a specific project, they can’t go to the public or to a foundation or to a business and ask for money. They can accept the money, but it is harder on their end, to then restrict that money to specific projects. So that’s where we come in: is number one, we can do the actual fundraising and the asking for the money. But it’s also much easier for us to say, you know, we’re doing this specific project. And a donor comes along and says this is exactly what I wanted to go to. And we can help them sort of facilitate that restriction on their end; it’s just a little bit more difficult because they’re a federal agency.

Gotcha. So basically, not only can you ask for money, you can actually come up with ideas that you think are worth implementing, and you can get around some of the red tape, and then help implement it.

Yeah, exactly. Right now, a lot of the support that we’re providing is either funding support, or volunteer support, or really marketing support —you know, telling the stories of our parks and getting people interested in all the different aspects of our parks, because that’s not really what the Park Service does. But in the future, one of the things we could be able to do is actually manage some of the projects. So that’s also what tends to happen in parks — particularly if they’re struggling to staff, their parks, like a lot of other businesses are. So, sometimes it’s not always about the money, it’s about having themanpower to manage a project to get it complete. And so that’s another role that our friends group will probably play in the future: getting sort of actual project management support to get things done.

And by that, I mean, like volunteers and things like that, or do you mean like hiring people to do the job?

Yeah, like actually contracting the work. And again, we have all kinds of agreements with the park service, and rules that we have to work within. But, for example, if we were doing a construction project, and we could do the contracting separately from the Park Service, then that gives them a little bit of leeway in how we how quickly we can get those projects done. If you don’t have to go through a process.

Because they’re basically strapped, too. They’ve got a bunch of stuff going on. So you can take a lot of weight off of. And they’re strapped not just for funding, they’re strapped for time, they’re strapped for all this stuff. You guys can come along and say, “Alright, this is something that we want that — that public says will make a great idea for this park — let us help implement it, and we’ll connect them in it from finding the funding to do even contracting the work.” It sounds like.

Yeah, we’re not quite there yet. But that is kind of one of the long term goals that provide that kind of support.

And is it safe to say is that this is basically how all friends groups operate? I mean, is that kind of like their mission statement for a friends group in general? Is just to take on these jobs and concerns that the park either can’t do? Or because they’re not allowed to or it just doesn’t have the time or resources to?

Yeah, I mean, I would say on a basic level, yes, that’s kind of the goal of what most of the friends groups are doing or providing. It really it depends, per park, almost all friends groups are doing some form of fundraising. And then they provide varying levels of support based on their park’s needs. So that’s what’s kind of unique about it; they get to sort of adapt their operations and what they work on and their mission based on what their parks need. So I know some — particularly urban parks — that have really strong, in-depth volunteer programs, and the friends group actually manages the whole volunteer program for them. You know, a lot of friends groups give actual education programming, so instead of the park having to hire seasonal staff to give ranger programs or give tours or things like that, the friends group has staff that can actually do that on their own as part of their agreement with their parks.

So the type of support I think, varies by friends group, but the basic goal is that we’re all here to just protect and enhance our national parks in any way that they need. And it is pretty unique here on the Outer Banks, for our size committee to have three significant national parks that have national significance — not only in their stories, but Cape Hatteras is up there among some of the highest visitation parks.. And so I was really excited personally, to see this organization come to fruition. And like you said, I know Superintendent Hallac has been a huge support. I’ve worked very closely with him and his team, as we’ve been getting this thing off the ground.

Do you guys lobby at all? Do you do any political activism in defense of the parks in any way, shape? Or form? Is that, uh, is that separate?

So we can do advocacy on behalf of the parks. So just be there to educate state legislators and federal legislators, about issues concerning our parks, talk to them about potential funding for Park projects —we certainly can do that. We don’t do lobbying, per se. But like I said, more of an advocacy education role, that is something that we definitely are kind of dipping our toes in right now.

That’s interesting. For sure day on day, hopefully Dave’s forgotten this, but the first time I ever spoke with Max he was as on a group call, he’s introducing everything. This was when I was doing a lot of work with Surfrider and offshore drilling issue was heating up pretty heavy and, and I asked him to take on that, and he gave a really nuanced answer. You know, I kind of stuck it to a little bit. But you know, is defense, the DOI makes these decisions, and that’s the park service’s boss. So in a situation like that, could a friends group be more vociferously opposed? At the same time the park might be a little more, you know, pragmatic.

I would say yes, and no. So the way that I like to approach our work is that we want to be a true partner to the park. So I am not going to go and say anything that’s going to somehow reflect badly on our park or isn’t aligned with what they sort of their messaging or their mission. At the same time, we do have a little bit more freedom to say things that they maybe would not feel comfortable saying, because they are a part of the federal government. So yes, and no. So before I go to any sort of, you know, advocacy, meeting, or just even thinking along an advocate line, I always talk to the park to make sure that we’re aligning our message and our priorities with their message and their priorities, because I just, I feel like that’s what a true partnership is. And that’s what we want our work to be with the park,

I thought was another interesting you said earlier, like, the public private partnership. Can you go into that a little bit more? It’s such a buzzword. It seems like, in a world where people are leery of ‘handouts’ for lack of a better term, public private partnership seems to be a great way of going about it. Can you give a little more detail on that, and how that how that works?

Yeah. And that really goes back to sort of the origins of philanthropy and the national parks. So if I remember correctly, I think it was actually at Acadia National Park. They were one of the first parks that received a donation of land to actually start their park. And so that really kicked off what is public private partnership and philanthropy look like for national parks, and that was well in the early 1900s. But, yeah, I think that’s really the basis of what these friends groups are made to do is to be able to provide the public — and even, you know, private foundations, private businesses — the ability to support these places that are very special to them. So you know, I think for me, when I think about our national parks, they’re providing such an amazing experience here on the Outer Banks. And having Cape Hatteras National Seashore have 70 miles of protected beaches, is I think a big part of why our community is so special and why it’s different than other East Coast beach communities, right? So we’re not Virginia Beach, we’re not Myrtle Beach. And that’s partly because we have a National Seashore that’s protecting our land here. And so I think people know that, and understand that, and have a deep connection to these places, and the experiences and memories that they’ve made here. And they want to be able to support them.

And like I said, the park on its own, while certainly you could walk up and give a donation, it’s not as effective as having a friends group that can be out there really focusing on projects, really getting different types of stories and messaging out and engaging the public in a different way that the park just doesn’t have the capacity to do. So I think that’s kind of the basis of why we’re here, right? Is that public private partnership. And they’re a federal agency, but their federal budget is just sort of the baseline of funding that they can get. There’s other federal funds out there. And those pots of money are built for that public private partnership to encourage that.

And so that’s a role that we can play; we can bring a match that allows them to get more federal funding. So are not here to replace their budget, right? That’s never going to be our role. It’s really just to fill some gaps and to allow them to access additional funds when they need it.

Can you give me some examples, then? I mean, of stuff that you’ve had going on? People and groups you’ve worked with? And can you sort of break down more success stories?

Yeah, so I think the biggest sort of partnership project that we’ve been working on is our Pathways to Your National Parks campaign. And the first part of that we kicked off last year, and that is to help build a new multi-use path at the Cape Hatteras lighthouse. So that will connect route 12, to the Old Lighthouse Beach site and to the current Lighthouse with a little over a mile of paved multi-use path. And what’s really interesting to me, when I when I talk to the park staff is that is a project that has been on the books somewhere, sort of on their wish list, since 1984, I believe. And they just didn’t have funding, they didn’t have capacity — all of these things – to be able to make that project really happen. And so it was one of the first projects that we started talking to them about when we founded and launch Outer Banks forever, in 2019. But you know, we were still a new organization. And it was a pretty big project. And so we were like, “Okay, let’s keep this in mind. But we need to build sort of our base of donate up donors and support.”

So when we started to really kick that project off, in 2021, one of the first donations that we got was from Cape Hatteras Electric Co Op. They are, as of right now our top private donor. They gave a $30,000 donation to specifically get the construction design started for this project. So that was a huge, partnership. And the Cape Hatteras Electric Co Op couldn’t give that money to the parks, but they could give it to us. So sometimes there are restrictions on the funder side of who can actually give to the National Park Service, and we can play that facilitator/mediator role. So they gave the donation to us, and then we gave it to the park for that project.

Same thing our next biggest business donor is Real Watersports. They have been giving consistently since the beginning. Trip Foreman is one of our founding board members. He’s currently our board president. And obviously their business is based in the Seashore. So without the National Seashore, their business would look very different. And so he and his team have felt just really strongly that they want to support the park and support projects like this pathway.

So those are kind of our two biggest donors. Like I said, we have a great partnership with Swells’a Brewing. They’re doing, they signed up for the 1% for the Planet program, which is a really great program. It’s a global program, any business around the world can sign up. And basically they dedicate 1% of their sales each year to an environmental organization. So we had already started working with Swells’a, we were doing our Pints for Pa”rks events. And then they decided, You know what, we want to kind of double down on this and go for this 1% for the Planet partnership. And so they signed up for that. And they just gave us a donation of just over $11,000,which is really exciting.

What a great way to help! Just drink a beer!

Exactly. Those are kind about some of our big funders. We did also receive a $25,000 capacity building grant from the National Park Foundation. So the National Park Foundation is sort of the official philanthropic partner of the National Park Service as a whole. And they have a variety of different grant programs that we’ve benefited from. But one of the biggest was a grant that actually allowed me to bring on a part time staff person, who now is full time, but just kind of given us that boost up. So National Park Foundation was a big supporter. And then just a couple others: so Carolina brewery, we have a great partnership with them. Robert Poitras has lived here off and on throughout the years, he is on our board, they gave a great donation to the Pathways Project. Even before that Ocean Atlantic Rentals and Towne Nank teamed up to help us do our very first projects back in 2020, which was creating a mobility-friendly kayak launch at Oregon inlet. So it was actually the first dedicated kayak launch in Cape Hatteras National Seashore. They didn’t have any dedicated kayak launches, until we partnered with Ocean Atlantic and Towne Bank to get that done. So we’ve had a really good outpouring of support from local businesses. But really our a lot of our fundraising comes from individuals and families. So that’s what we mostly focus on. We do have a good local donor base, but mostly visitors and second homeowners who are just really passionate about the parks, and love what the parks provide, as far as both protecting resources and telling historical stories. So that’s kind of really our bread and butter with individuals who have this great connection to this place and our parks here and want to get back to him.

Do you know how much money you’ve raised since you started?

I can give you an estimate for sure. Let’s see… actually, this might more accurate, better number to give people some perspective. This year, we are going to be giving the parks about $400,000 for the Pathways Project and several other smaller projects.

That’s amazing. And so tell me more about those projects. And you already mentioned the kayak, one you talked about the path was where we were where were we in the process and the pathways, and then they said, You were done with the fundraising side, you’re under the implementation or what’s the sort of chronology?

Yeah, so for the Buxton pathway we are, we’re just kind of wrapping up the final push for the fundraising campaign right now. So April, in May, will be kind of where we wrap that up. So just last month, we got to review the 65% complete construction drawings from the contractor. We did a walkthrough, made a few edits, put some comments back to them. So we are expecting to get the final design drawings in the next month or so for final review. And then the goal right now is to have the fundraising campaign and the design finished in May, so that they the park can then go to contracting in June. It is quite a lengthy contracting process. And you know, anything construction related these days takes a little longer. But our goal right now is that they will start construction in early 2024.

So you got that and the kayak, and what other projects you’ve completed? And what’s the what’s on the done deck?

Yeah, so I’ll start with the ones that we’ve completed. And I’ll tell you a little bit about some of the things coming down the pipeline. So last year at Fort Raleigh, the volunteers to came to the park staff and came to us and said, ‘We would love to put in an education garden right beside the visitor center that talks about the importance of agriculture on Roanoke Island specifically for the Native Americans that lived there, the English colonists when they first came to settle, as well as the Freedmen’s Colony which was formerly enslaved of families who lived on Roanoke Island after the Civil War.” So they wanted to have three part-education garden. And we said, “Yes, absolutely.” And it’s this, you know, really new, fun, unique way to tell that story. So we completed that last year, they got a couple more things they’re gonna add to it this year. But that was a really fun project.

We also we partnered with the Outer Banks Visitor’s Bureau and Surfline, and we helped put a webcam up on the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, so people can see the view from the lighthouse wherever they are. And that was pretty exciting. That project is really a three part project. We are going to hopefully put one at Wright Brothers, we’re working on that right now, to have a webcam up on top of the monument. So you could kind of get that beautiful view from up on top of the monument. And then there will be one at Fort Raleigh, as well, that will look out on the sound. So those have been really fun.

The ones that we have coming up, we are working on an artist and community project with the parks. So national parks — particularly the larger national parks around the country — many of them have artists residency programs, where both local and national artists can come and do their whatever medium their artwork is, in the park sort of be inspired by our national parks. And we didn’t have that here. But we know that we have a very vibrant local arts community here. And I think you’d be hard pressed to walk into any art gallery and not see at least one of our lighthouses. So this artisan community event that we’re going to have on Earth Day, which is April 22, will kick off what we hope will grow into a true artists residency program where we’ll be able to help support those local and potentially national artists in the future, who are inspired by our national parks.

We also working on a new Freedom Trail for Fort Raleigh. This will be a new education trail for people to experience it specifically talks about the Freedmen’s colony. So I think Fort Raleigh, it’s best known as the site of the Lost Colony. But the Freedmen’s colony, like I said, was a community of formerly enslaved families who came to Roanoke Island after the Civil War and had a community there for a couple of years. And so this New Freedom Trail is really going to expand on that story. Some, you know, again, it’s one of the stories that I feel like most people don’t know about Fort Raleigh. So we’re really happy to be supporting that.

And then, over the next couple of years, we’re going to be working pretty extensively on a couple projects at Wright Brothers National Memorial. So back in 2019, the Park Service, worked with the community and they redid their general management plan, which is basically the strategic plan for Wright brothers that said, “Here’s kind of what we have, here’s sort of what we’d like to see in the future.” And we’re in kind of the early discussions of how we might be able to help them with a couple of the bigger projects, which include a new education building. So right now, the Rangers give programs, particularly to school groups, either inside the visitor center, which can be a little bit of a challenge, or outside under a temporary tent. And as the site of the first flight, and with the Wright Brothers story being such an integral part of the history of the Outer Banks, we’d love to see a true education building where they could do larger school groups, and have weather-protected ways to give the public different education programs. So the education building will be a big one. And then we are going to put a new multi-use path around the property at Wright Brothers, which again, will just be a new way for people to experience. Right now, there are some sidewalks that are kind of connected. But we really want people to get a full view of the entire property at Wright Brothers and be able to have a new way to experience it. So we will be working on a multi-use path there as well.

That’s crazy. And so what percentage of these different projects would have been funded if you guys didn’t exist?

I think, these types of projects get funded down the line; it’s just sometimes can take a lot longer if they don’t have a group like us to find the additional funding that they need. So when we think about, for example, the pathway down in Buxton, the park was able to get a $1.3 million grant from the Federal Highways Commission. Then there was just a little bit of gap in the funding, which is where we stepped in to sort of fill that gap and raise about $350,000 for that project to get us to the finish line. But I would say most of these projects would be on a long list that the park and the community would love to see. And the park would be able to maybe get one or two of them don’t a year, particularly with the smaller projects, but for some of these larger projects, I think we can just accelerate both the timeline and just sort of the feasibility of actually making them happen.

Not just from a financial standpoint, but also because you’re dedicated to that one, cause you’re not split up with whatever else the park service has to juggle. And then I guess any long term goals? Like fundraising numbers and the like?

Yeah, I think it’s, again, it’s gonna depend as we prioritize projects with the parks, but I feel like our long term goal is really to be providing sustainable financial support to meet the park’s greatest needs and help them adapt to new challenges and new opportunities that come along. I think that’s one of the things that is just hard for parks because, like you said, there they are concerned about capacity, how many people that they have to be able to manage the parks, and really the day to day operations/ Sometimes they don’t have the opportunity to say, “Okay, what else is coming, you know, coming down in the future? And how can we help?” So, really, that’s kind of my goal, I don’t necessarily have a concrete fundraising goal, because I think it will just depend on which projects we make a priority each year. But, really, it’s just to provide that sustainable financial support, to meet the parks’ greatest needs, and help them adapt. Because I think we live in a very unique community, we live on barrier islands. So there’s lots of things that we have to adapt to here. And like I said, I think that’s one of the things we’ve been able to do as far as the increased visitation, is giving people new ways to experience the parks, to learn about the parks, and then also to be able to give back, because like I said, I think people feel very connected to this place, and they want to support it and make sure that future generations of their own family and others can come here and have those same experiences. And that’s what we’re here to help facilitate.

So how do people help? How does the fundraising work? And when you say you’re getting missive mostly from visitors and whatnot? Is it are there like boxes placed around? Is it? Is it a membership, like what sort of the way it’s people can actually help?

Yeah, so we, we do have at least one electronic donation box that’s set up inside the Visitor Center at Wright brothers. But primarily, we started by just building an email list, so folks can sign up for our email list, and once a month, we kind of send out an update with some interesting stories and behind-the-scenes looks at the parts. And that’s where we’ve gotten most of our donations. We also do mailed newsletter. So folks prefer, you know, kind of print something to read. We do that twice a year. And that’s where we get donations as well. So, if people are interested, going to our website is the first place to start. We’ve got lots of great information there about upcoming events, like I said, behind the scenes, stories, things that they may not know about their national parks, we’ve got articles there that they can check out. And then I think signing up for our email list is really the best way to stay in touch about the projects, specifically, and be able to donate.

And one of the great things I think about what we’re able to do, is we can do donor recognition in our parks. So that’s something that we, as their official philanthropic partner, are allowed to do. So for example, with the pathways campaign, once you get to the once the project is complete, there’ll be a donor wall there – you know, just small —but it’ll recognize the folks that have given to that project. So we’ll be doing more of that, depending on what the project is and where it’s at.

So, a Trip Forman Tribute Footpath? Is that what we’re talking about?